Who's afraid of a fake influencer?

Fictional TikTokers, the roaring maw of corporate try-hards, and my daily routine

When I first read about the fictional influencer industry, my initial response was, Why? Vox profiles a tech-entertainment company called FourFront, which enlists writers and actors to fabricate TikTok creators; the company has raised $1.5 million in seed funding and boasts what founder Ilan Benjamin calls an “MCU-style universe of characters on TikTok.” Accounts span a range of social media archetypes, from army dad to empowered sugar baby to the Vox article’s focus, a “broke 20-something” named Sydney who works for a dating app and posts “insider” advice. The characters’ story arcs veer towards the cinematic— a boyfriend who’s secretly a prince, the discovery of a 20-year-old son— but the writers’ room is careful to document the banal as well. Veteran Chris, who just learned about his long-lost son, talks into his front-facing camera while he grills meat and mixes up the terms “negging” and “necking.” Carmen, the sugar baby, is Sydney’s roommate; they do each other’s makeup in their cramped, undecorated bathroom, their Brandy-Melville-pretty faces mirroring each other. When Carmen pans to Sydney to explain how she “hacked’ Carmen’s dating app metrics to produce hotter dudes, Sydney is mildly annoyed, hesitant to speak candidly on camera.

While Benjamin insists that “every one of [his] characters is openly fictional,” his creations are designed to quietly assimilate into your feed. Only recently did FourFront’s accounts start adding a #fiction tag to their videos; as someone who recently tagged a meditation video #PradaBucketChallenge, whatever the fuck that is, because it was trending, I’d say it’s safe to assume that most viewers don’t seriously consider hashtags to be descriptors or disclaimers. Sydney’s dating tips were picked up and shared by the Mirror, and then the New York Post, as fact.

On a visceral level, I find the notion of a studio-backed actor pretending to be a broke 20-something sort of patronizing and shitty; I’ve written before about the internet’s complicated relationship with truth, and I think most consumers find corporate relatability endeavors equal parts cringe and sinister. More than that, though, FourFront seems unnecessary: Why would you employ an actor for a part almost anyone would take for free? It’s not like online personalities are known for their moral fortitude or their brand discretion. Remember when those influencers agreed to cyanide sponcon? FourFront’s plans are apparently to “license their AI character voices to other companies, and to make money with some kind of subscription model or by selling tickets to live events starring their characters,” which feels like an expensive expansion of the already successful influencer meet-and-greet model. Why create an entire industry when you could just be a talent manager?

Or maybe, the online personality industry already exists— we simply control the means of production. We curate, edit, create, delete, and FaceTune. I mean, what is fiction? Is choosing the right lighting so different from tweaking a photo with Photoshop? Should we add a disclaimer to stories that aren’t filmed at the time of posting? We all pretend. Some of our motivations are aesthetic, some precautionary, and some stem from the natural desire, online and off, to become whatever’s most easily consumed, most easily loved.

I’m inclined to think that FourFront exists, in part, to sate film bros’ weird entitlement to a piece of the cool girl pie— hi, manic pixie dream girls— but I also think that in creating fictional influencers, FourFront sidesteps human error. Their characters won’t ever get themselves cancelled, or fight in the comments, or decide that they simply don’t want to influence anymore. Unlike real influencers, FourFront’s characters will never burn out.

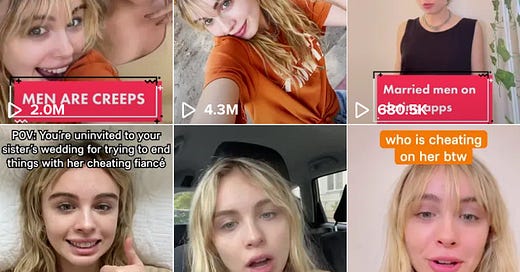

After I read the Vox article, I performed my daily ritual of deleting text attachments off my hard drive and uninstalling and reinstalling various apps. I work exclusively from a constantly at-capacity MacBook Air, because I’m deranged and because I can’t afford a desktop. While my computer restarted, I shuffled my to-do list, pushing things into the future. I wondered whether today was the day I finally ran out of ideas. I checked my bank balance, tried to remember which invoices were paid when, which bills were bimonthly and what month it was and how full my gas tank was and whether I needed to go anywhere. I dug my old EDD card out of my wallet and called the number on the back to see if I still had a balance. I opened TikTok to check on a video that had been erroneously dogeared as violating their user agreement; I’d appealed, but the appeal had been pending for weeks and TikTok was threatening to deactivate my account. TikTok has a creator fund, to support artists, and I checked that, too. Over a two-month period with over 200k likes, I had earned exactly one cent. I opened Instagram, filtered my dms to “unopened,” and watched them load: Dozens, and then hundreds, of jokes and compliments and complaints and cat pics and rape threats and expired story tags. I opened the requests folder and found this diptych:

I’m so, so, so lucky. And also, my second response to that Vox article was, Let them have it.

This isn’t to say that I resent or regret my creative path. I don’t. I care deeply about creating and creators, which is precisely why I think it’s important to critique the model. Regardless of talent or worthiness, FourFront’s existence acknowledges that to be extremely online requires an immense amount of labor. It’s marketing, copywriting, comedy, graphic design, small business economics, video production and editing. It’s the nebulous art of parasocial charm, not unlike when I waitressed and learned to flirt without making eye contact. Honestly, I’m not always good at creating. (See: My perpetually unread dms; my perpetually empty bank account.) In this way, FourFront is deeply validating: There are producers, actors, and writers for a job that I’m constantly told I should perform alone, for free. I should be better and faster. I should feel lucky that anyone even likes it. Content creation is the fastest-growing form of small business, and I worry that the industry’s rapid growth and veneer of accessibility allows for a job market in which employers and consumers undervalue the work.

And also, in avoiding the messiness of humans, FourFront forgets that human messiness is what makes social media so compelling in the first place. This isn’t unique to FourFront, or even to branded accounts; there are dead-eyed narcissists and rote try-hards and industry plants all over the civilian internet. But there’s also Taco Bell date girl, and Noodles the pug, and that British guy who grows really big vegetables. At its best, the internet is a living being, collaborative and weird and open to the milieu of human experience. It’s where the main character can be played by a character actor, or an understudy, or someone who just stumbled onstage. A corporate entity will never doubt whether they’re supposed to be there. A fake can’t feel terror mixed with glee, the wind in your hair as you surf a 60-foot wave of dread. A brand won’t achieve 4.2 stars on Wikifeet. I’m not an idiot; I suspect that FourFront is troubleshooting the human-but-not-human problem as I type this. I do think, though, that we’re in an important between-space, where the creator model hasn’t gelled yet. We still have time to redefine what this work means for us, and to push back against whatever creepy corporate hack comes for us next. What if instead of developing facsimiles to compete with the creators who inspired them, we just paid creators what they're worth?

ahhh lonelygirl15 and internet girl's staged youtube spiral reminiscent!!! and im sure many others ; but it is interesting how throughout time folks have looked to pay young females to perform these very specific roles of casual suspended disbelief... when there are plenty of us just doing it for real in real time