The panopticon, the psychosexual struggle between social media and reality T.V., and us

We’re both more attuned to and more wary of producer manipulation, but we're unreliable narrators of the stories we tell about ourselves.

I didn’t use the five or so hours Instagram was down wisely. I scrolled Twitter, where everyone was dunking on Facebook and Instagram, and I thought about how dunking on something can be a socially acceptable way of staying fixated on it. I put “vintage - 2000s” jeans in my Etsy cart, knowing I’d never buy them. In anticipation of a future afternoon outside my apartment, I googled whether Costco hot dogs contain pork. (In America, they do not.) And then, on TikTok, I discovered a feed of minute-long clips of I Love a Mama’s Boy, a TLC reality show in which girlfriends clash with their cowardly boyfriends’ overbearing mothers. I dipped in and out of the chaotically intertwined storylines, re-watching clips to remember which crazy mom demanded which wedding theme and to read the comments (“run girl!”), until the Australian account holder apparently went to bed. I tried to unlock episodes on Hulu and the TLC website, and when that didn’t work, I purchased four more episodes, one after another as the credits rolled, for $2.99 a pop on my family Amazon account.

As a genre, unscripted television is deceptively broad: Wikipedia lists 20 reality sub-genres, including “Financial transactions and appraisals” (Pawn Stars, Antiques Roadshow); “Special living environment” (Big Brother, The Simple Life); and “Hoaxes” (Undercover Boss, My Big Fat Obnoxious Fiance). I Love a Mama’s Boy is a “Subcultures” show, a niche that aims to “shed light on rarely seen cultures and lifestyles.” TLC excels in the mass aggregation of individuals with “rarely seen lifestyles,” from Toddlers in Tiaras to Sister Wives to Breaking Amish to Little People, Big World. Personally, I feel a little weird about “Subcultures.” These shows glibly package themselves as opportunities for representation, but their narrative framing often keeps the viewer at ogling-distance, concerned more with sensationalizing a subject’s experience than empathizing with it. (A rare exception to this may be Netflix docuseries Love on the Spectrum, which follows Autistic adults navigating dating and relationships with what seems, at least, like genuine respect and care.)

I’m not sure, then, why I couldn’t stop watching 32-year-old men say “But she’s my mom.” In my defense, on the vast spectrum of on-camera exploitation, I Love a Mama’s Boy feels slightly less icky than TLC’s usual fare. For one thing, the show films choices, rather than identities; these women can dump their boyfriends, these men can set boundaries, these mothers can stop trying to sensually tango with their sons at their sons’ weddings. For another, by the second season, at least, it’s hard to imagine that everyone involved isn’t at least a little in on the joke. Truthfully, though, I think I got a contact high from the drama, and from the mere act of watching something supremely embarrassing. No one knew where I was, or what I was doing. I didn’t owe an unpacking or a hot take to anyone. Instagram was down – for once, I wasn’t being watched.

Of course, that isn’t true. Of course I was being watched. But Instagram is my biggest audience; as my follower count has grown, what felt at first like an arbitrary number on a screen – pixels rearranging themselves in some loose choreography with my posting schedule – has become an entity of its own: A pair of eyes over my shoulder, a copyeditor flicking at my thoughts with a red pen.

On The D’Amelio Show – a series that could best be described, according to the Wikipedia list, as “Soap-opera style,” like an extremely wholesome Anna Nicole Show – the TikTok behemoths and their internet famous friends often discuss what might get them cancelled. They compare which of them can say what, generally agreeing that none of them (all girls) would get away with the behavior of your average hype house heartthrob. The D’Amelio sisters come off as sensible, reserved, maybe even a little boring. It makes sense: scrutiny has been ingrained in them, early and intensely. In one episode, fellow creator Quen Blackwell, visiting for a private hibachi dinner, says of this self-checking: “It’s this third person that’s not existed to any other generation.” She points at the camera, laughs. “That. It’s in your head all the time.”

Lying in bed, the blinds cracked, watching 56-year-old Kelly don a Lady Liberty costume to announce that she’ll be crashing her son’s girlfriend’s birthday trip to New York City, I felt free. I felt like a middle schooler watching Next! before my parents got home. I knew that later, I would feel the godless loneliness that I wouldn’t call depression until my early 20s. But in that moment, unbound from expectation, all I had to do was kill time. We talk all the time about the beauty of being a speck in the vast universe; we rarely appreciate that being a fly on the wall can also feel like stardust.

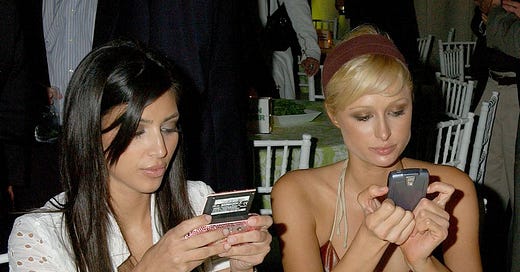

Shows like I Love a Mama’s Boy are a dying breed. I don’t think this is a bad thing, per se, but I do think it’s interesting, and I think it’s important to consider how social media has accelerated that decline. TLC’s ouvre echoes the energy of early 2000s MTV unscripted, the gleeful exploitation of people willing to ham it up for ratings to the point that they’re almost – almost – complicit in their own public humiliation. Regular people were dropped into surreal circumstances, exalted or humiliated, and then dumped back into their normal lives, like the show was some cosmic wormhole that maybe paid you a day rate. The appeal of reality – they’re just like us! – feels charmingly dated now that social media has collapsed the barrier between subject and audience in ways a TV screen never could. This also means that the subject and audience have an unprecedented ability to affect one another. This is revolutionary – it means that the subjects of reality TV (who are, in their civilian lives, members of the audience) are adapting to this new reality landscape faster than producers and studios. Contestants are wiser to a producer baiting an unsavory sound bite, aware that production’s investment ends in its profit return, while the consequences of televised bad behavior can follow them for years.

The result of this, at its best, is kind, weird social experiment T.V. like The Circle, which should be the most dystopian show on television, but has turned out to be among the most tender. The Circle isolates players in private apartments from which they can only communicate with other players, and only through an eponymous in-show social media app. Contestants play as themselves or as catfish, and compete for a $100,000 prize by ranking each other; the most popular players become “influencers,” who then have to “block,” or disqualify, another player. Season 1 premiered January 1st, 2020, and will best be remembered for eerily foreshadowing the claustrophobia and digital dependence of quarantine. The show was also formative, however, for how it subverted the expectation that reality competition is brute sabotage. We watched winners agonize over who to send home, and losers tearfully forgive the people who eliminated them. The social manipulations – if you could even call them that – resemble less the alliances of Survivor and more the tacit negotiations we all make when we’re trying to get someone to like us. Every season, a catfish is revealed, and the players shrug. They tell the camera that they love the person they met in the chatroom, even if they don’t look like their profile picture. The show feels less like a money grab, and more like a docu-series on how a disparate group of strangers kills time alone in their apartments, and how they – and we – find human connection on the internet.

If The Circle is about regular people pretending to be influencers, The Bachelor is about influencers pretending to be regular people. The franchise, known for its love of romance novel iconography and polyamory-but-make-it-Bible-belt format, has run since March of 2002, and it shows. It took over 20 seasons for the show to reckon with its deeply problematic relationship with race; former Bachelorette Rachel Lindsay deftly unpacks these biases and blind spots for The Cut, and honestly, her take should be required reading for anyone who’s read this far. Additionally, the show is struggling to update both its relationship to technology – while filming, the cast generally pretends that the internet doesn’t exit – and its brand of cutthroat heterosexual resource anxiety.

We recently saw a watershed moment in a two-episode arc of summer spin-off Bachelor in Paradise, when contestant Brendan admitted on camera that he’d strung along fellow beach-goer Natasha for more followers on Instagram. The Bachelor-to-influencer pipeline is a straight shot – the right edit can set a contestant up for a lifetime of sponcon deals. Of course players are thinking strategically about their socials. The rules of the game, however, have been the same for nearly two decades: when the cameras are rolling, you’re there for love.

Brendan’s open conversation around social media was a franchise first – and so was the audience’s reaction. After the episode aired, off the horny beach and in the real world, his actions lost Brendan roughly 100,000 Instagram followers; Natasha gained over 300,000 followers. This may seem like a superficial gesture, until you remember that Instagram is where the contestants’ careers live and die: Brendan also lost at least one sponsorship deal. Honestly, he truly was being an asshole, so I’m not really mad about it – but the experience was a unique confluence of the television and internet worlds, evidence that audiences are tired of seeing unrepentant assholes in media and aware that their voice can be even louder than the network’s.

It’s hard to imagine a world in which networks can continue to alternately throw their talent to the wolves, or protect them from their own realities. (On the subject of the fate of old-guard reality shows, it feels germane to note that two of TLC’s cash cow franchises, Here Comes Honey Boo Boo and 19 Kids and Counting, were upended when the public exposed male stars who had sexually abused children.) In April of 2021, TikTok surpassed YouTube in viewing time per user; our dominant media is social media, and if what makes you a darling to producers demonizes you to the public, why would you ever risk a villain edit? According to a blog post by I Love a Mama’s Boy subject/beleaguered girlfriend Kim, only one of the show’s moms has social media at all. It’s a private Instagram account with 439 followers.

Nothing lasts forever. Instagram came back online; I can’t deactivate in any serious way, because it’s my job, and my cathartic outlet, and also I’m addicted to it. I Love a Mama’s Boy started to feel like what it was: artificial, insufficient, a potato chip when I want a french fry. To quote another reality titan, “There’s people that are dying.” Watching people unravel just doesn’t feel fun anymore, especially when I know a team of people is on the other side of the publicly unwell, getting their lighting right. Why would I watch a dramatic reenactment of the voice in my head?