Carl Dreyer has this line I love, something about using artifice to strip artifice of artifice. Dreyer’s best known for directing The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), a brutal and beautiful exploration of the saint’s inquisition and eventual burning at stake. Tossing out the script he’d been given, Dreyer turned instead to the real— the film is lifted directly from the transcripts of Joan’s 1431 trial for heresy, improbably real and improbably preserved in Paris’ Bibliothèque de la Chambre des Députés.

Bizarre as it feels to attribute my favorite take on synthetic value to a 1920s silent film director over, say, anyone who existed alongside the internet, The Trial of Joan of Arc is a masterpiece because of its creepily modern ability to evoke emotion through alienation. Filmed entirely in close and medium shots on one continuous tessellation-like set, with mismatched takes that would flunk a first-year film school kid, the film is disorienting, unsettling, and eerily intimate. You, like Joan, are seeing things you don’t know how to talk about.

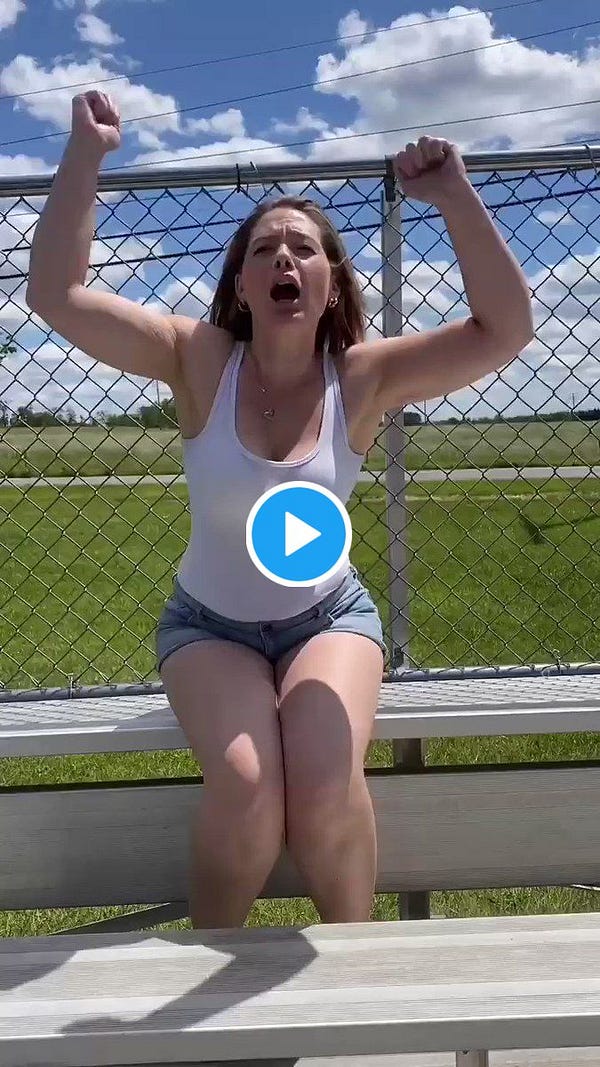

A century later, I’m thinking about Angel MaMii. With her children and her partner John Dees— yeah, I’m pretty sure, as in Dees Nuts—Angel has spent the last few years unlacing the language of online comedy, creating sublime, surreal content where plotlines swell and shift and disintegrate in 30 seconds or less. Watching an Angel MaMii video is like staring into a mirror and screaming your own name until it doesn’t mean anything anymore, in a good way.

The videos are entirely improvised, and they’re aware that they “don’t make sense,” Angel and John told the Daily Dot in a 2020 interview. The dialogue often feels like the conversations you have in lower level foreign language classes: Where is the library? My aunt loves to read and to fish. She has forty-eight years. Shot in anonymous spaces like supermarkets, parking lots, and big box stores, Angel MaMii’s films echo The Passion of Joan of Arc’s intentionally unplaceable set; John told the Daily Dot, “Someone suggested that these were good locations because the algorithm likes them, and that’s why we initially started at stores.”

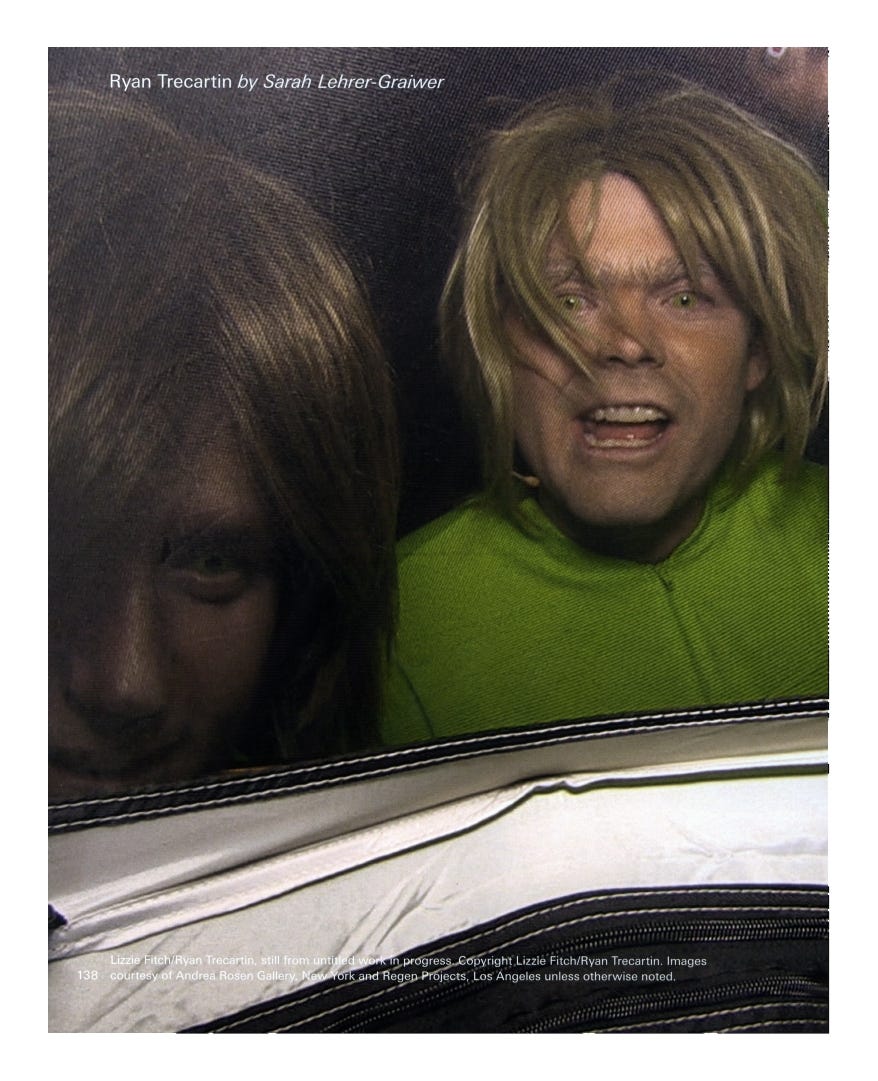

The closest contemporary I can think of is video artist Ryan Trecartin, whose stilted delivery and hallucinogenic dialogue evoke the same dizzy giddiness. His work lacks Angel MaMii’s intimacy, perhaps because it’s inherently more polished, more art world— In 2006, Trecartin was the youngest artist to present at the Whitney Biennial— but employs the same delight/horror dynamicism. What feels like Angel MaMii’s standard vibration, however, is a meticulous process in existential upheaval for Trecartin: he’s spoken in interviews about cultivating a practice of “intentionally temporarily forgetting” his past work, so he can focus on present projects; he likes to move his studio and office spaces as often as possible, and to include decades-old cutting-room-floor clips in his contemporary projects. His practice is hyper-collaborative, often the product of several camerapersons wandering a location. The bizarre, sprawling video work that comes out of this process feels deeply contemporary and also unattached to time and space, floating just a few inches above our cultural consciousness. Trecartin says of filming, “We started focusing more on context as being the main character of the movie, rather than on individual personalities. And we used different characters and their behaviors as tools and utensils for the free will of the context rather than of the individual.”

What is the language of online performance? With Angel MaMii, as with Trecartin, it’s a Greek chorus: the work feels important— and even futuristic— in its plurality; both artists often utilize multiple performers and filmers. Beyond the participants, however, Angel MaMii’s videos in particular have a user-generated quality, like she’s metabolized a decade of college improv bros and YouTube influencers and Saturday morning cereal commercials into a sort of visual hyper-pop, glitchy and forceful and weird and deceptively intimate. At the same time, in an economy of relatability, Angel MaMii’s content is inimitable. While social media sometimes feels like a million-student-body performing arts academy, mediocrity is rewarded over excellence; what’s the purpose of an algorithm, after all, if not to determine and amplify the median? And yet, I haven’t seen any other creator make consistent content in a voice like Angel’s. When a Twitter user pointed out that Angel follows David Lynch, the internet gleefully suggested that he make her a muse in upcoming projects. I’m a fan of Lynch’s work, but honestly, Angel MaMii doesn’t need him.

The most incredible thing, maybe, is that while they resist easy interpretation or commodification, Angel Mamii’s videos are still so fucking fun to watch. She’s been making these since 2019—why hasn’t the schtick gotten old?

The answer, maybe, goes back to artifice— the Sim-gone-rogue shellac belies— or slyly emphasizes— an immortalizing sincerity. While the average TikTok relationship has a sheen of transactionality that ranges from blithely corporate to deeply unsettling, Angel Mamii and John Dees seem, improbably, to actually be in love. They met at a TikTok creator meetup— arguably an artifice summit— but their rapport feels like the sort of back-and-forth nothing pillowtalk you have at 3 in the morning with someone who’s peed in front of you a hundred times, the self-evident delight of being weird around someone you love more naturally than you love yourself.

Carl Dreyer was a tyrannical director, forcing Falconetti to kneel on stone for hours while rearranging her face into a facsimile of placid faith. He shot and re-shot the same scenes endlessly, until the actors were exhausted and the lines robotic, stripped of craft. He said of his process, "When a child suddenly sees an onrushing train in front of him, the expression on his face is spontaneous. By this I don't mean the feeling in it (which in this case is sudden fear), but the fact that the face is completely uninhibited.”

I think, on that one— on inhibition— Dreyer missed the mark. Toiling can be a kind of cheat, too—a workaround when you can’t kickstart inspiration, the “fuck it” of giving up when you can’t summon the “fuck it” of joy. The role was Falconetti’s first and last film appearance.

Maybe the future of content is collective in a way that will upend the asshole auteur trope. Maybe there’s space for the cheekily oracular, the collective fever dream; the shocking, romantic experience of witnessing people doing the weird shit that makes them happy.

I first heard that Dreyer quote about artifice in conversation with a poet friend for a lit mag a few years ago; since then, I’ve used the line to explain my favorite media and own work. I looked it up while writing this, to get a sense of context, but I could only find it attributed to Dreyer as quoted by other poets. No origin. It’s possible Dreyer never said it at all.

In The Passion of Joan of Arc, the inquisitors want to know what God promised her. She can’t say, exactly; she isn’t a prophet-on-demand. Knowing she’s going to die doesn’t lessen her fear of death. She is extraordinary because she’s human. When asked her name, she says, “In my country, they called me Joan. In my village, they called me Joanie.”

Roger Ebert writes of the film, “Perhaps the secret of Dreyer's success is that he asked himself, ‘What is this story really about?’ And after he answered that question he made a movie about absolutely nothing else.” Angel MaMii’s work feels the same way, except it’s about nothing, that centering of context. While she’s been filming for years, I don’t know that I was truly ready for her until now, when I feel individually fragmented and culturally never more connected to our big, grieving whole. What’s everything, about except making something out of nothing, anyway?