Measuring Forever

Donnie Darko, time travel, and the Jurassic Quest Drive-Thru Experience

I had a dream the other week where my therapist (who wasn’t my therapist) told me to repeat the affirmation, “I will love the mysteries of life that turn out to be truth.” I remembered this in standstill traffic, sucking my vape pen, watching an animatronic T-Rex bend and rise over an animatronic bloodied Stegosaurus. It’s hard to receive a cryptic message and not consider prophecy.

My choice to attend the Jurassic Quest Drive-Thru Experience was made in the existential panic phase of edible consumption, when I compulsively make plans to cement that there will, in fact, be a future for me. Pre-pandemic, Jurassic Quest was “North America’s largest and most realistic Dinosaur event,” a semi-educational promenade of 100+ robot dinosaurs that seemed to hover somewhere between Natural History museum and amusement park. Now, the dinosaurs were set up in a stadium parking lot, and you slowly drove past them, listening to their surprisingly well-produced theme song (and some less expertly produced dino commentary) from your phone or laptop. You couldn’t touch the dinos. You couldn’t smoke. You paid by the car, not the person, the fiscal irresponsibly of which I didn’t take into consideration until I later realized that it wouldn’t be logistically or medically sound for anyone to join me, though the high price point and draconian refund policy meant I absolutely had to follow through. My ticket included a non-optional “family” photo opportunity.

I wasn’t even trying to travel to the Jurassic period. I wanted, I think, to access a more recent past: an experience of childhood wonder.

It’s funny that humans are so concerned with the mechanics of time travel, when we’re traveling all the time—in repetition compulsion, in rumination, in anxiety forecasting. The heart racing, the mind blank. I feel like I’m constantly visiting or creating other dimensions, searching for a secret key to unlock whatever butterfly effect could lead to a holistic, productive present. Idling at a squeaking feathered something with a long Latin name, it occurred to me that the flexibility—and precarity—of time feels more apparent now than ever, both in the day-to-day sense and in our place in the greater Anthropocene, our collective crisis of witness to our inevitable extinction.

My first exposure to time travel was Donnie Darko, the psychological thriller magnum opus for emo teens who believe they’re smarter than their friends. I say “exposure,” and not “understanding,” because the whole movie is canonically un-understandable. (For a thorough plot breakdown, I recommend Donnie Darko: The Tangent Universe, a website that in itself feels a little like time travel.) The Richard Kelly thriller was released in 2001, but it’s an aesthetic journey to 1988, rife with yuppie parental friction and throbbing synth. It’s a subverted Brat Pack film: a mean guy with a mullet snorting coke in the locker hall, a quietly unhappy nuclear family, benign Americana—Donnie has a Led Zeppelin poster and an American Flag on his ceiling, the way a porn set would have a mirror—until Donnie is lured, pied piper-like, out of his home by dystopian hallucination Frank the Bunny. Donnie and I both get messages in our dreams. In his, he’s told to destroy various property of The Man, like his high school and the home of a pedophilic motivational speaker. He’s also given a prophecy: the end of the world, in 28 days, 06 hours, 42 minutes, and 12 seconds.

I watched Donnie Darko over and over again as a teen, not caring that I didn’t get it because I was busy being horny for Gyllenhaal. Longing feels inherently adolescent, not because it’s immature, but because I don’t know how to access it anymore. I have yet to find the portal that takes me to a place where I want so hard it physically hurts. Where do those wires cross—the threshold between emotional and physical ache? It’s all synapses in the brain, I guess, some sinister chemistry to help us survive. This is important to mention, because the logic of Donnie Darko isn’t the logic of science; it’s the logic of a crush. Donnie can’t tell if he’s reading into things. His obsessions consume him from the inside out. He sees signs everywhere, unable to separate prophecy from paranoia. Love and fear may be on either end of the life line, but both fuel psychotic thinking.

In order to save the world, Donnie must travel through a wormhole, sacrificing himself in the process. This plotline feels like a wormhole into the present; we have apocalyptic countdowns of our own. Last September, New York’s Metronome—a 62-foot-wide, 15-digit electronic clock overlooking Times Square— stopped counting 24-hour-cycles and started counting the time remaining before our environmental impact becomes irreparable.

Then there’s the Clock of the Long Now, the stuff of blockbuster sci-fi: a leviathan clock funded by Jeff Bezos and built into the side of a mountain. If all goes to plan, the clock will measure 10,000 years. It will tick once a year; every millennium, a cuckoo comes out. It is completely unhinged.

The Clock of the Long Now was first imagined by computer scientist Danny Hillis in 1986—two years before the end of the world in Donnie Darko—and remains under construction. (Coincidentally, Hillis’ other projects include his own quest for a robotic dinosaur.) Its construction requires the decimation of the interior of a mountain on one of Bezos’ properties, in Texas’ Sierra Diablo Mountain Range. Wikipedia suggests that the interior of this mountain is somewhere between 300 million and one billion years old. Blasting it apart to build a testament to 10,000 years seems profoundly human.

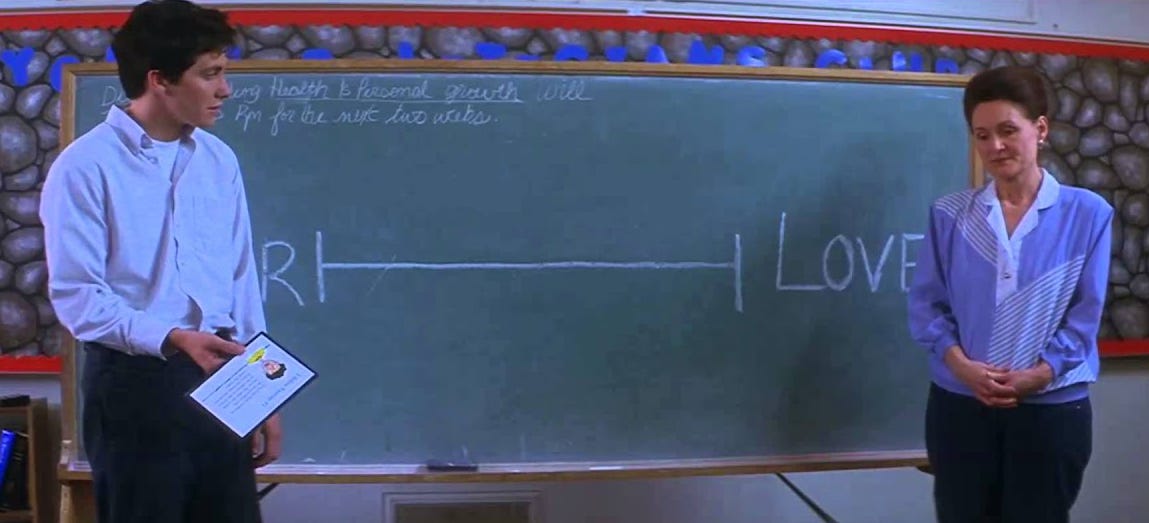

Traveling from 2021 to Donnie Darko is delightful, but it’s also cringe. There’s the romanticized mental illness, the casual racism, the intellectual softcore. The least realistic aspect, however, and the most grating, to me, is Donnie’s absence of fear. Donnie wanders suburbia occasionally horny and mostly curious. Even the (weirdly bootstrappy) rants he delivers as he unravels are performed with confidence. In one scene, his class watches a corny PSA on “fear survivors,” satirizing the pointless and embarrassing media of any high school health class. But isn’t that the ultimate act of bravery— to survive fear? To see who we are on the other side of this?

How do we measure the future? How do we know which mysteries of life turn out to be truth? And, more practically—what’s the point?

Stewart Brand, a founding board member of the Long Now Foundation, says of the 10,000-year clock, "Such a clock, if sufficiently impressive and well-engineered, would embody deep time for people. It should be charismatic to visit, interesting to think about, and famous enough to become iconic in the public discourse. Ideally, it would do for thinking about time what the photographs of Earth from space have done for thinking about the environment. Such icons reframe the way people think.” This goal—to reframe the consequences of our actions as generational, rather than immediate; to help us metabolize the vast scope of human existence, so we better survive—is noble. It also seems entirely undermined by Bezos’ participation in the project. Jeff Bezos is either the kind of evil billionaire who will throw millions of dollars into a clock-shaped hypothetical before he allows his workers to unionize, or he’s the kind of evil billionaire who plans on watching the countdown to apocalypse from a far-off Kindle Fire screen.

So much of science fiction gets it wrong. Popular visions of the future often depict it as sleek and minimalist, white and chrome. These surfaces seem laughably uncomfortable now, unable to conform to the human body as the human body taps to order groceries and a dick appointment. We know the world is coming to an end; the question of whether we’ll sacrifice anything to change that is another story. At the end of the Jurassic Quest Drive-Thru Experience is a gift shop. My ultimate takeaway is that to experience dinosaurs, you need to burn a lot of fossil fuel.

We will love the mysteries of life that turn out to be truth, and the ones that never turn out. To see the future feels less important than to see what the future could be.

“Frank,” Donnie Darko asks the bunny, “When’s this gonna stop?”

Frank responds, “You should already know that.”

love this one but missed opportunity to shop yourself into the movie theater